[Originally published in eldiario.es on 3rd March 2015 and kindly translated by Richard McAleavey ]

The metamorphosis of Podemos

When the monster awoke one morning following a torrid dream of elections, it lay on its bed, transformed into one more party of rule. There it was with its hierarchies, its internal posts, and its phony rhetoric. It was now a party for cynics, destined to contain the democratic tide, rather than be washed over by it.

Such is the party-driven nightmare that many of us participating in Podemos have sought to highlight from the beginning, when we set our desire on electoral victory as the immediate political horizon. If Podemos must be a party in order to break the locks on the institutions, let it at least be a party different to all those it seeks to evict, both in the way it functions and in the things it proposes. The journey of representation means taking on baggage that may prove uncomfortable, but some of it can be an unnecessary burden that we would do well to avoid.

Obviously, we must keep in mind the limitations and the peculiarities of the sphere of political representation, as I wrote nearly a year ago. It is as illusory to pour scorn on the breaches that can be opened up from within the existing institutions, for which we have to adapt to the rules of a game that we ourselves have not defined, as it is to think that it is exclusively the Party or the State that brings about democratic change – least of all in one country, as Syriza is very well aware. Moving within the frame of what is possible, winning elections, which took Syriza a decade, does indeed require an electoral ‘war machine‘[i].

What is less clear, however, continuing this war metaphor, is whether this machine works better in the manner of national armies of old, or whether it should be understood based on the innovations and lessons that networked insurgencies have provided. What is even less clear is whether such a machine would then serve to develop good government (the “what for” that ought to complement the “winning”). To win seats in parliament requires a competitive logic; a good democratic government requires a logic of co-operation.

Since Podemos unveiled itself in January 2014 as a ‘method for participation open to the entire public’[ii], the initiative has evolved to the point that it has formalised as a political party. This constitutive process finalised on the 14th of February passed following the election of the different internal posts on a national level. However, with regards to the process of organisation, and in an electoral context where prospects are good, the debate frequently took the form of a war waged in personalised and binary terms, between fans and trolls. This internal rancour was fed in part by the establishment of a system of internal lists and voting that did not correct the existing inequalities in terms of access to media resources, but rather took advantage of these inequalities, albeit without acknowledging this openly. But it is not as simple as this.

The preoccupation with ‘internal democracy’, or to put it another way, with forms of internal-external interaction and communication that do not merely go in one direction, is not the product of the fear of winning or the inability to win, and it is not liberal scruples that take no account of the particulars of what we are building or of what is at stake in strategic terms. This preoccupation is legitimate because it emerges from what we have learned about the party-form after a long historical experience, not from self-serving theoretical abstractions. It is legitimate, moreover, because it is faithful to the ultimate objective that moves all of us who have set out on this adventure in good faith: contributing to a real democratic rupture. The way in which we organise ourselves and treat each other within the Podemos environment prefigures in many respects the way in which a Podemos government will be organised and how it will relate to the public.

In many ways, Podemos is currently more democratic than other parties, but it is also true that there has been a consolidation of a mode of operating in which the decisions tend to come from the centre so as to be rubber-stamped by what had initially been nodes that had a degree of meaningful autonomy. This tendency has not been consolidated completely, due to territorial diversity, due to the margin allowed by the gaps in internal regulations, and to the informality that still characterises a good deal of relations inside the party, as a consequence of its particular origin and its initial development.

What is true is that until summer of 2014, or perhaps until the citizen assembly in Vistalegre, Podemos was overflowing at every level, with different constitutive and militant elements (television spokespersons, Anticapitalist Left, circles, sympathetic activists etc.) interacting with a social ecosystem influenced in large part (but not completely) by television. As we know, the electoral success of the 25th of May placed the media focus definitively on Podemos, and, in the context of an accelerated political decomposition of the regime, Podemos began to occupy centre stage. It forced all the other parties to use its terms and its methods, albeit in a purely rhetorical manner. This being the case, the main preoccupation, in organisational terms, of the group that developed around the leadership of Pablo Iglesias, consisted of controlling this overflow, out of fear (reasonable in some cases, excessive in others) of entryism and the ‘appropriation’ of the brand -on a local level, for example- for different ends to those declared by the main leaders. The problem is that this intent on control, along with the way in which it has been practised, can end up mystifying the possibilities for empowerment and effective participation, thereby limiting the very effectiveness of the political strategy that has been set out.

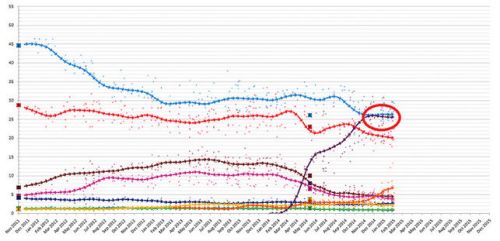

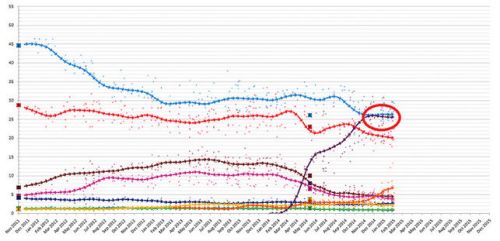

One fear, already present since the beginnings of this project, is ‘if the project is presented in terms of representation, presupposing the homogeneity and the unity of the body it must head up, it will cancel out its own conditions of possibility‘[iii]. Well, this risk appears to be materialising before our eyes. A glance at the evolution over time of all surveys (see the interesting graphic below that is regularly updated on Wikipedia) shows how growth was vertiginous in the run-up to the European elections, less so but still very significant during the September-November process of constitution, only to stagnate since then, even following the successful mobilisation of the 31st of January.

Should things continue like this, even were Podemos to win the next general elections, it may not do so with the resounding victory needed to kick off a constituent dynamic driven from below. Even victory at the elections itself is open to question, despite decent surveys, given that the Spanish electoral system, when it comes to parties at State level, rewards parties that win over 25% and punishes those below this level. Podemos currently oscillates in and around this percentage, which is relative and a function of the degree of growth or collapse of other forces. Hence it is worrying to encounter the self-satisfied reading according to which the surveys ‘unanimously show an upward trend, at a vertiginous speed, and if we manage to maintain this ascent we will be in a position to govern, possibly with an absolute majority[iv]‘. As we can see for ourselves, this assessment is incorrect, as is also the insinuation that the rapid upward growth is exclusively down to a small team.

That is, from the citizen assembly onward we have witnessed a slowing of the growth of Podemos, though for the moment it is still benefiting from the deterioration of the PP, PSOE and IU. Another symptom is the diminishing participation in internal electoral processes, despite the rise in the number of people signed up (this may also indicate that those participating are the most recent arrivals, whereas many of those who took part initially are now abstaining). This slowing down coincides, moreover, with a decided withdrawal, as a consequence, on the one hand, of internal electoral processes, and, on the other, the growing subordination to the agenda of television stations that are currently sympathetic but whose fundamental task consists of normalising the phenomenon. Firms such as Atresmedia and Mediaset have their own interests, in accordance with which, for example, they frame the content of what must be the object of public debate. The current promotion of Ciudadanos in these media outlets also goes in the direction of preventing a broad majority for Podemos and filing off its rupturist edges.

Undoubtedly it is dizzying to think how far Podemos has gone in such a short period of time. Today the betting favours Podemos because it has positioned itself as the new winning horse, because it is the only option in the running that seeks a rupture with the regime of 78 and has possibilities of governing at State level and in various regional governments. And even were the least favourable results in the polls to become reality, they would still amount to an unprecedented historical event. It is logical to try and preserve positions that have been won and to avoid false steps now that a distorting microscope looms over Podemos and complicated decisions are on the way following the next regional elections. But to be satisfied with this is a dangerous invitation to lead the opposition. Once the novelty has worn off, might it not be the very fact that Podemos is finally recognisable and predictable, that is, less monstrous, what now makes it more vulnerable? Is it reasonable to tone down proposals for the electoral programme, or cast aside as marginal ideas that are feasible and at the same time innovative -constituent- as is the case with those that bring a transformative quality and those that would oblige other forces to make a move? Does respectability entail looking more like what you are criticising, or does it rather mean taking this criticism to its ultimate consequences?

These observations do not deny that the electoral fray is still wide open. They merely express cautiously that the political task that confronts us is enormous. It is for this reason that it is worth asking the new state-wide Citizen Council, whilst recognising the great deal of good it has achieved until now, that it conduct a serious reflection on the shortcomings of the present strategy and on what can be improved, not only with a view to winning the elections but also to anticipate the future actions of government in the European framework. In order for Podemos to gather together a broad social (and hence electoral) majority the party will need to avoid closing in on itself, and to seek formulas that lead to new overflows, new viral effects. This representative majority will not be achieved merely by attracting old voters or activists from the PP or the PSOE or IU, but also all the various abstentionists who when taken as a whole constitute the main ‘political force’ in the country. It will mean winning over but above all listening to and incorporating not only those who see themselves as middle class despite their precarious position but also the poorest of the popular classes, those with the least education, for whom abstention is structural. It would not be a bad thing to have more plebs and less party aristocracy. It is possible to involve people in the formulation of proposals for substantial change that they can treat as their own and not as measures desired exclusively behind their backs by an elite. After that the details of how it gets set up and its practical application will always be technical and the work of people with the necessary training; a great deal of work has already been done here, both in the university and in the movements. It is not enough, then, to denounce corruption on TV and avoid committing errors.

Podemos has not finished its metamorphosis. The tale can be different to what those who are satisfied by the current state of things are hoping for.

When the party awoke one morning following a torrid dream of elections, it lay on its bed, transformed into a monstruous tool for democracy….

[i] Link to remarks by party strategist Íñigo Errejón in October 2014. Errejón is now Political Secretary of Podemos

[ii] Link to initial Público report on Podemos launch, January 2014

[iii] Link to January 2014 article by Pablo Bustinduy, currently member of Podemos Citizen Council

[iv] Link to remarks by Luis Alegre, current Secretary General of Podemos in Madrid region, 10th February 2015, during campaign for Secretary General post.